| Maryland Newsline |

| Home Page |

Politics

|

| Black Doll Artists Reclaim

a Rich History

Maryland Newsline Friday, March 11, 2005 BALTIMORE - When Lisa Queene was growing up in Annapolis, Md., all the dolls she owned had white skin and blue eyes. Then, in 1968, Mattel introduced a brown-skinned Barbie. But Queene, who is African-American, wasn’t sure she liked it. “These black dolls were foreign to me,” said Queene, who was 13 when she got one. “I guess I was conditioned at that time to accept my white dolls and to just like them.” Queene, 46, is now one of a growing number of artists who create dolls that embrace their black tradition. Many of these dolls, ironically, are not intended for children but are collected by adults as art pieces at prices edging into the hundreds of dollars. As doll collecting grows in popularity, so has the dizzying variety of doll-making techniques. Doll artists can modify vinyl dolls to create a “reborn” doll, as Queene does, or sculpt their own original designs from clay, porcelain and other materials. They can aim for an eerily realistic look, or go for “an abstraction of the pretty little doll,” as does Adrienne McDonald, a Baltimore artist who makes a line of eccentric rag dolls called Urban Faeries. Doll making is an art rich in the African tradition. For generations, most dolls in African-American households were handmade because manufactured black dolls were hard to find or were too expensive, said Barbara Whiteman, a doll collector and the director of the Philadelphia Doll Museum, home to more than 1,000 historical and contemporary black dolls. “Culturally, we’ve always had challenges locating dolls that look like us,” McDonald said. A lot of black kids, she and others said, don’t grow up with positive images of themselves—or with ideas of what they can aspire to be. Both adults and kids learn from dolls, whether antique or modern, handmade or mass-produced, Whiteman said. “For us, dolls represent artifacts of history and culture,” Whiteman said. “And they tell a story of how black folks have been perceived through world history. Each of these dolls [has] a story.” 'Vessels' of Their Work

Now there’s even a book to collect some of those stories. “Black Dolls: Proud, Bold and Beautiful,” edited by Nayda Rondon of DOLLS magazine and published last fall, documents the work of 49 black doll artists around the country. Whiteman wrote its introduction. The book features one artist from Maryland, Paula Whaley of Baltimore.

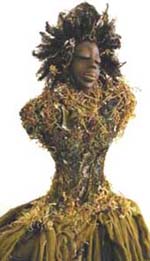

Whaley, who is in her 60s, said she started sculpting as a way of surviving the emotional devastation caused by the death of a beloved brother, writer and playwright James Arthur Baldwin. She works and sleeps above the display space for her dolls, in a one-bedroom apartment converted from a cluttered antique shop on North Charles Street in Baltimore. She calls her collection “Oneeki,” a Yoruba word from Sierra Leone meaning, “Treat her tenderly for me.” The name conjures up the vulnerability that comes from entrusting a loved one to another, like when a daughter is married into a different clan, she said. Tiffany Tate, a doll collector, owns three Whaley pieces among the almost 40 dolls she has scattered through her Owings Mills, Md., home. She also owns five by McDonald. “The dolls seem to have souls,” Tate, a public health consultant, said of Whaley’s work. “They can speak to you or remind you of someone or of a time or a phase you were going through.” Whaley uses natural fibers like cotton gauze, burlap, moss and palm tree leaves, husks and sticks to create different textures on her dolls. She molds their faces with clay, always with their eyes closed as if in prayer, and sculpts their hands with a synthetic material that allows for finer details than natural clay. “I’ve never made a doll all the way through,” Whaley said. Sometimes she just makes clay heads for a whole month, she said, and puts them away in a drawer. Whaley, who holds art workshops for children, does not make her dolls for them. “It just never occurred to me because of the way I got into it myself,” Whaley said, sculpting as an outlet for grief, Whaley said. “It was about me and my survival and about my trying to heal.”

In contrast to Whaley’s ethereal work, McDonald’s fabric dolls can look ugly to some people. To others, their unkempt hair, worn clothing and eccentric accessories suggest toys that have been loved into old age; like the Velveteen Rabbit, they are dolls that have become real. McDonald, 43, moved to Baltimore two years ago to escape New York’s high cost of living. Not yet at home here, she often escapes over the weekend back to New York. Fascinated with the people – some homeless, some not – she saw on the New York City subway during her 14 years in the city, McDonald set out to capture their mystique in her dolls for adults. “I mimic a raw urban environment,” McDonald said of her work. “That’s definitely my specialty.” Part of the rawness comes from dyeing her dolls with tea and coffee to make them look like “something your grandmother could’ve played with,” said Whiteman of the Philadelphia Doll Museum. But the uniqueness of McDonald’s pieces comes from more than just their stains. McDonald soaks stainless steel safety pins and bobby pins in bleach until they crust with rust, with rainbow colors peeking out from behind the brown grunge. Then she strings the pins like a heavy necklace around her dolls’ necks and waists, sometimes threading the pins in turn with luminescent beads, buttons and seashells. Some dolls have their necks wrapped high with tiny beads. Few, if any, have facial features. The effect is oddly charming, rough and feminine at the same time. Both Whaley and McDonald, who know each other, speak of forces that guide them toward these dolls, making the artists more like “vessels” than creators, as Whaley puts it.

“It’s almost like I’m outside of the work, looking in,” Whaley said. “I’m in awe of what’s developing and what’s coming through, also.” And both women emphasize the role of their ancestors in lending their dolls their peculiar qualities. Born and raised in Harlem as the youngest of nine children, Whaley even pastes a poem about ancestors on some of her pieces. “We know our past, but sometimes we forget it,” Whaley said. McDonald sells her dolls for $300 or more, and Whaley’s pieces sell for $500 and up. They arrange viewings by appointment and also place their work in art galleries and stores from New York to California. Both Whaley and McDonald started their careers in the fashion industry in New York City. Whaley joined B. Altman and Co., the first large-scale department store on Fifth Avenue, in the late 1960s, accessorizing mannequins and styling window displays. McDonald designed costumes and accessories for entertainers like Bill Cosby and Prince. Both decided to put their years of fashion experience into a passion for doll making. McDonald used to sew colorful rag dolls for children that would retail for $120 at New York specialty stores, she said. After a few years, her pieces naturally evolved into more ornate, adult versions that have proved more lucrative, she said frankly. Reflecting a Diverse Community

Queene of Annapolis spends her evenings making dolls that reflect the multiple skin tones of racially mixed children in her community. Her dolls aren’t for kids, either, she said, although a couple of parents have bought them as toys. The speech pathologist with the Baltimore City Public School System mixes her own dyes for the babies’ skin, hand paints their faces and often painstakingly inserts their hair, root by root. She takes apart their bodies, sometimes replacing their middles with soft stuffed fabric so that they feel like real infants. Her larger, 20-inch dolls usually sell for $140. Even when Queene makes white dolls, they come in different shades ranging from peaches-and-cream to olive. “It reflects what people really look like,” she said. Randy Allen, a former chief diversity officer at Kmart, said kids need dolls that look like themselves, because dolls inspire them with ideas of who and what they can be. In honor of Black History Month in February, Allen’s start-up doll company released two vinyl likenesses of Harriet Tubman, a "conductor" on the Underground Railroad, and Bessie Coleman, the first black American woman pilot. Each $65 doll comes with a bound biography. Schools and parents have been snapping them up, as have individual doll collectors, Allen said. To Whaley, a doll’s color shouldn’t matter at all. “I think we as a black people should have something we can identify with,” Whaley said. But with colors and cultures mixing more than ever, she said, today’s children reach beyond skin color for their ideas. Copyright © 2005 University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism

|