| Maryland Newsline |

| Home Page |

Politics

|

|

Digital Library Preserves Fading Cultures for Younger Generation

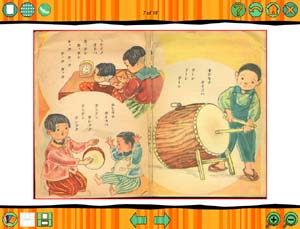

Maryland Newsline Tuesday, April 20, 2004 Lino Nelisi writes in a dying language. Her children’s books about life in New Zealand are written in her rapidly fading native South Pacific tongue, Niuean, then translated into more than six languages. Until four years ago, most of Nelisi's books circulated only in the Pacific region. Now, with two of her picture books included in the International Children’s Digital Library, readers from around the world can browse her stories. The ICDL is the only children’s library on the Internet and houses hundreds of rare, antique and foreign children’s stories from around the world. Developed by the University of Maryland’s Human-Computer Interaction Lab and the nonprofit Internet Archive, the children’s library connects cultures at the click of a mouse. Stories are written in 23 languages, from Finnish to Farsi to French.

The library makes books from less-developed communities accessible to the world, said ICDL principal investigator Ann Weeks, its self-described librarian. “People want to have their cultures represented, and being a part of the Web is a good way to get validated,” added ICDL Director Jane White, who works for the Internet Archive, which since 1996 has been building a digital library of historical collections. In the United States, minority groups are also scrambling to have their cultures included online. Native American communities are rushing to preserve their cultures and languages so they can be passed down to younger generations, said Betty Marcoux, assistant professor of information studies at the University of Washington. Marcoux and others at the university are working with Native American tribes in the Northwest to include their children’s books in the digital library. “It’s an obvious opportunity to allow Native American children to be empowered, to think they, too, can contribute something valuable,” she said. The library also includes books dating back hundreds of years, including a Finnish book about religion published in 1543. Many older books at the Library of Congress, including “The History of Insects,” first published in 1813, are delicately bound and brittle with age. “We’re preserving access to that book by keeping these books alive and available,” White said. The digital library’s plan is to collect 100 of the best children’s books from 100 countries—for a total of 10,000 books, White said. So far it has 324 books, scanned and donated by libraries and publishers around the world. About 40 percent of them are older classics, while the rest are modern books.

The ICDL’s original purpose was to study children’s responses to a digital library, but before the research groups could do that, they had to build one. For about a year before the library launched online in 2000, the groups worked with the Human-Computer Interaction Lab’s KidsTeam--a group of child researchers between the ages of 7 and 11--to determine the best designs for kids. Nelisi began writing children’s books 10 years ago when she couldn’t find multicultural literature to read to her New Zealand elementary school students, who hailed from around the world. But the award-winning author’s purpose wasn’t limited to writing stories that portrayed brown-skinned children. It’s equally important for non-Pacific Islander students to read Niuean-New Zealand stories in order to appreciate and respect the various languages worldwide, she said. “At the end of the day, the world is not made up of one culture,” said University of Maryland’s KidsTeam founder Allison Druin. “The world is made up of many cultures, and books are the best learning experiences we have.” Copyright © 2004 University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism

|