|

|||||

| Politics | Business | Schools | Justice | Health | Et Cetera |

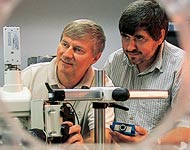

By Rachel Mauro Two-dimensional objects observable by miscroscope, that is. Christopher Davis, a professor in electrical and computer engineering, and Igor Smolyaninov, a visiting research scientist from BAE Systems, use a 10-micrometer “cloak” made of special gold and plastics to manipulate the light around an object hidden inside. The light bends around the object, similar to how a stick would look bent if placed in water, Davis said. When you look directly at the cloaked area, it appears that nothing is there. You might not be able to wear the cloak, but “you can carry it around” in your palm, said Smolyaninov. Patrick O’Shea, chairman of the University of Maryland’s Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, noted scientists have dreamed of conquering invisibility ever since 19th-century author H.G. Wells wrote “The Invisible Man.” Because their work so far has been in two dimensions, it has “limited applicability,” O’Shea said. But, he said, “It’s still very interesting from a scientific standpoint. It bodes well for future work.” Davis said the technique may also work in three dimensions for simple, geometric shapes, but not for something complex, like a human. Davis and Smolyaninov discovered the invisibility effect while studying plasmons, which are waves of electron density existing in metal. The ripples from the waves are highly hypersensitive and can scatter light particles, both to create invisibility and increased visibility, they said. Two years ago, Davis and Smolyaninov developed a plasmon microscope using beams of plasmons to magnify tiny objects without the use of expensive equipment. Now, they want to study plasmons in more detail and see if their hypersensitivity might lend itself to other research, like genetic testing. Plasmons can detect genetic material when they are placed on a surface with certain biomolecules, Davis said. “Invisibility gets people’s attention, but as far as we’re concerned, our work has more practical utility,” Davis said. Though their findings are not officially published yet, Davis and Smolyaninov submitted their research in September to arXiv.org, an electronic archive hosted by the Cornell University Library in Ithaca, N.Y., where scientists can get feedback on their ongoing research. Other scientists gave them positive feedback concerning their work with plasmons. Girish Agarwal, professor at Oklahoma State University and a moderator at arXiv.org, said he thought it was “a good experiment” that brought invisibility to the visual spectrum where the naked eye could observe it. “I would think that we will see more and more practical implication of the cloaking idea in the visible, optical range,” Agarwal said. “We’re happy people liked it,” Smolyaninov said. The pair is working on a fuller paper for submission soon but have no further details on it, Davis said. In the meantime, they have already gained a small bit of fame over the invisibility factor. After the University of Maryland’s Clark School of Engineering published a press release online about the topic, media organizations ranging from a student newspaper to NewScientist.com requested interviews. “Suddenly, somebody caught hold of it, and it’s become an interesting topic for people,” Davis said. “Theoretical people have talked about it for quite a long time,” he continued, but building something like the invisibility cloak is much harder than discussing theory. In order to obtain the effect they want, be it invisibility or something else, Davis and Smolyaninov make two-dimensional patterns on the metal, which make the plasmon waves move in specific ways. They make these patterns using a technique called electron beam lithography. “We use electron beam lithography to literally write, on a very tiny scale, down to a few nanometers, the structures that we want,” Davis said. This technique is also used to create other tiny, inticrately designed objects like integrated circuits for computers, he added. “There (are) all kinds of unusual things you can do on these very, very small scales,” Davis said. “These plasmons and invisibility (are) just one of them.” Davis and Smolyaninov do their research in the Kim Engineering Building nano fabrication facility on the University of Maryland campus. Further development on the cloak depends on whether the team can get funding. Their research on plasmons to date has been funded through the National Science Foundation. Davis predicts that more funds may be difficult to secure, because of what he terms a “culture of instant gratification.” Some government agencies “just want to go buy a solution today. They don’t want to support research to have a better solution next year,” he said. “And that’s some of the fight we have to fight all the time.” Maryland Newsline's Rachel Mauro can be reached at techgadgets-online@jmail.umd.edu. | ||||||||

|

Copyright © 2007 University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism | ||||||||

| Politics | Business | Schools | Justice | Health | Et Cetera | |||