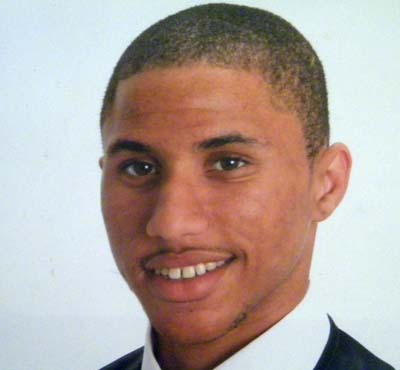

Michael Layne, 19, was a high school graduate who was about to start a job at the Government Printing Office. (Photo courtesy of Tracy Ellis)

Slain Temple Hills Teen Was in the 'Wrong Place at the Wrong Time'

Maryland Newsline

Monday, April 25, 2011

TEMPLE HILLS, Md. – Michael Layne was always well put together; he cared about his appearance and never left the house without looking his best.

His shoes always matched his shirt. He worried about having to get braces, again. “He had the prettiest teeth that cost me almost $5,000,” said his mother, Tracy Ellis.

For Christmas, he asked for a Polo jacket, which his mother bought for him while the two were out shopping. “He was like a shopaholic,” Ellis said. “When he was leaving the house, you would think he was going for an interview.”

Layne, 19, was wearing his Christmas jacket when a bullet grazed his chest Jan. 4 in the 4000 block of Norcross Street in Temple Hills, Md. The bullet did not kill Layne – the glancing impact of the projectile induced a fatal heart attack, his mother said.

Maryland law prevents the chief medical examiner from confirming the cause of death in a homicide case.

His mother said her son was coming home after playing video games at a friend’s house; the group was walking down the street.

Police said the shooting was part of an attempted armed robbery, perhaps motivated by drugs. Three of Layne’s friends were injured in the incident, police said.

Layne, who lived with his mother in Temple Hills, was arrested for possession of marijuana last June. The case was never prosecuted, court records show. His mother said Layne had not been using marijuana since a stint last fall in drug rehab.

No arrests have been made in his murder case, but Ellis said police have stayed in touch with her weekly.

And although police can’t give Ellis the jacket her son wore the day he was killed, she said, she does have a closet full of his clothes and shoes -- and notebooks that her son must have written in daily.

It’s not a lot of consolation for a life cut so short.

Layne had “started making some good decisions and deciding what he really wanted to do,” Ellis said. “I think that’s the part that really bothers me. He was taken away when our family was seeing … him developing into a man.”

‘Well Mannered’

Annette Nichols, a neighbor, said she had known Layne since fifth grade. She remembers him playing outside as a child, tossing a football around or riding his bike with other neighborhood kids. Nichols said her son, 21-year-old Anthony Nichols, was one of the children Layne often played with.

“We basically watched him (Layne) grow up,” Nichols said. “He wasn’t a troublesome kid at all; he was well-mannered. He would say ‘Hi, Miss Annette.’ You’d see Mike, he’d always speak. He didn’t cause no problems.”

Nichols said Layne would frequently go to the Marlow Heights Community Center to play basketball, a fact Ellis recalled as well. Layne cared about his physique just as he did the clothes he wore.

“He was in excellent condition,” Ellis said. “He played basketball every single day at the rec center.”

Nichols said Layne was in “the wrong place at the wrong time.” She worries about her own son, given the circumstances of Layne’s death, but knows there’s not much she can do.

“I just pray on it,” Nichols said. “My son, he’s 21, and he hangs out … but I just keep praying to God that nothing ever happens to him.

“It’s not good to be out on the streets during the night time.”

Generous with Time and Possessions

Ellis said she always knew when Layne wanted something new.

“When he was getting ready to ask me for something, he would come lay on my bed, and say, ‘Hey mom, what you looking at?’ I’d say, ‘What do you want now, Michael?’ ” she recalled.

Layne’s fashion-consciousness extended beyond his own appearance. Ellis said when Layne was out shopping, he’d always keep his 3-year-old brother, Gregory, in mind.

“He would say, ‘Mom, you need to get this for Gregory, that for Gregory.’ It was unreal,” Ellis said. A single mother, Ellis said her eldest son played a big role in helping raise his little brother.

“He helped me with everything,” she said. “He occupied his (Gregory’s) time, like while I was either getting rest, or just playing with him, being that big brother, showing him different things. Especially with getting potty trained.”

Layne was generous with friends, too. Ellis said one of her son’s friends didn’t have many clothes, so Layne would give that friend what he could spare.

“I would buy him T-shirts and underwear and stuff like that, and he’d say, ‘Mom, I need another pack,’” Ellis said. “He helped out. (His friend) didn’t really have anything.”

Tracy Ellis, Michael Layne's mother, talks about her murdered son. (Slide show by Maryland Newsline's Alexander Pyles)

After Layne died, Ellis said she gave away many of his clothes. Most of them ended up with that friend.

Tiera Cutler, 18, a close a friend of Layne’s, said his kindness extended to her, too.

Pregnant at age 16, Cutler said she was considering abortion after doctors told her the child had a chance of developing Down syndrome. Distraught, Cutler sought Layne’s advice. He told her to have the baby.

She did, and the 1-year-old boy is healthy, she said.

“He was such a good friend to me. He was always there. I would call Michael for anything, and he would listen,” Cutler said. “I can honestly say Michael is the reason why my son is here.”

Growing Up, a Budding Writer

Though he used marijuana for a time, Ellis said she could see her son starting to grow up. He finished home schooling last May and earned his high school degree.

Layne landed a summer job at the National Institutes of Health in the radiology department. Ellis works at NIH as a supervisory program specialist.

Ellis said Layne was supposed to start working in February at the Government Printing Office in the bindery department. He planned to buy a car once he made enough money – he told his mother he wanted a Monte Carlo, not realizing the old Chevrolet wasn’t going to be particularly fuel-efficient.

“He just wanted to be different,” Ellis said. “He wanted to have a different kind of car. I had actually planned to give him my other car once he got a job.”

Layne was still trying to decide what he wanted to do in his career, but Ellis said her son’s favorite subject in school was English. Layne apparently wrote a lot, Ellis said, which she only learned after going through his closet after he died. It was lined with stacks of spiral notebooks.

“When I was going through his room, I found a journal, I never knew he wrote in it,” Ellis said. “I haven’t had the courage to go and read everything in it. He has a lot of stuff in it. He wrote maybe every day.

“I used to wonder where all the spiral notebooks were going.”

Layne was apparently interested in taking pictures and video, too. For Christmas, he picked out and received a camcorder, his mother said. The camcorder is still in its box in Layne’s bedroom.

“He never even got the chance to use it,” Ellis said.

Coping with the Loss

Faced with using leave time or losing it at the end of December, Ellis took the last three weeks of the month off and spent most of that time around the house with Layne. She said she normally wouldn’t have taken the time in such a large chunk, but was glad she did this time.

She returned to work Monday, Jan. 3.

Layne was killed the next day.

Ellis has not yet given up hope that police will find her son’s killer, but she admits there are few good days for her emotionally.

She said she tries to visit her son’s grave at Fort Lincoln Funeral Home in Brentwood, Md., on Fridays.

In March, Ellis and her sister organized an event for friends and family to pass out Crime Solvers reward fliers in parking lots.

Ellis said everything reminds her of Layne; a camera he used frequently hasn’t been used since he died, and the CDs he used to listen to in the car haven’t been removed.

She’s stopped cooking – Layne’s favorite meals were fried chicken with corn and cubed steak with sautéed onions, gravy and rice – but going out to eat isn’t any easier.

Ellis said she knows she needs therapy, but hasn’t signed up. She said doctors have given her medication to help keep her calm.

It’s difficult, she said, but she tries to remember the things she is grateful for: Her son graduated from high school and was becoming a man.

“He was a wonderful kid,” she said. “All kids have their problems, but he was, like, the joy of our family.”